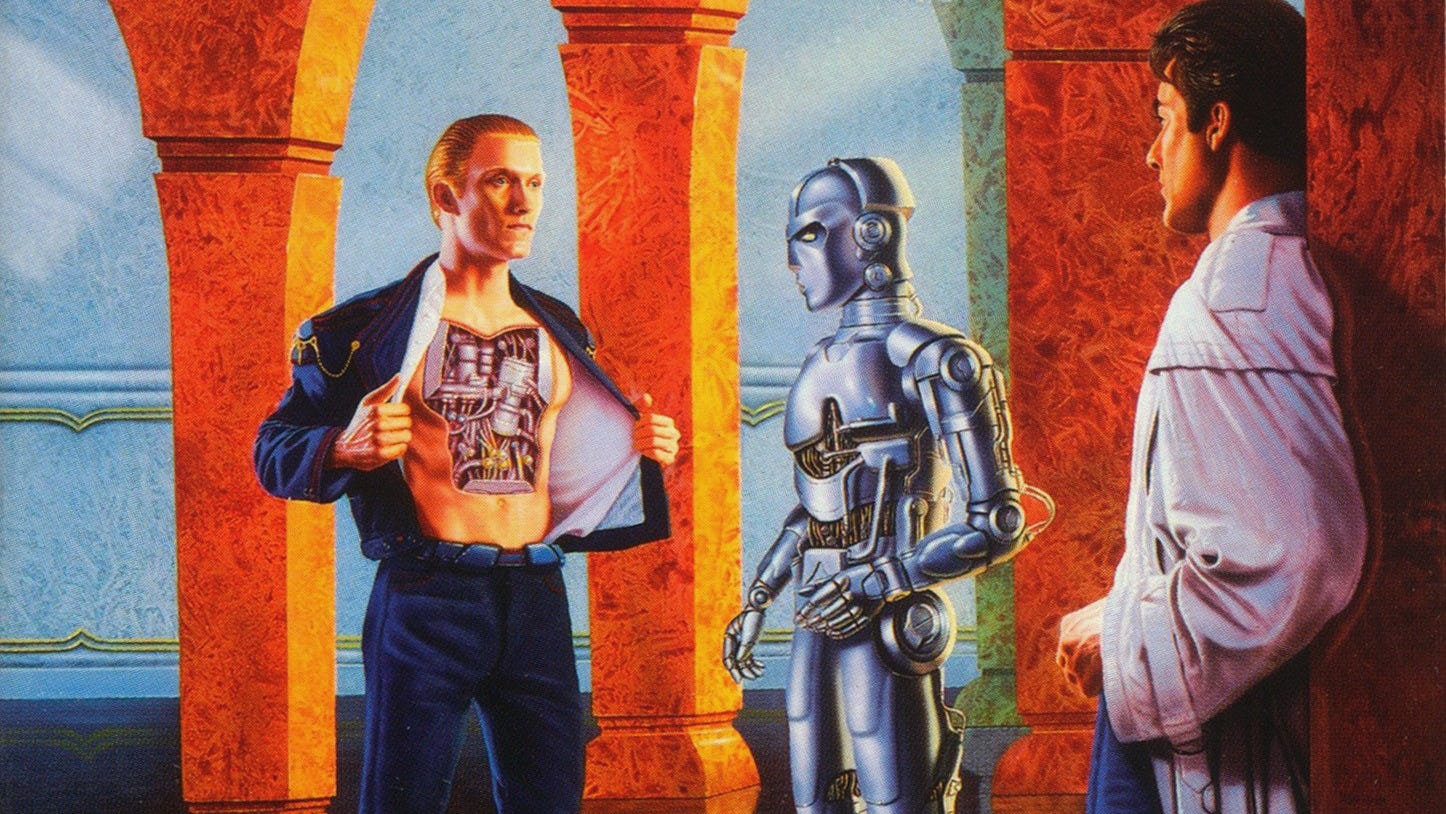

This image is the cover of the second novel in Asimov’s Robot series, The Naked Sun. The character on the left, R. Daneel Olivaw, exposes his reality as a robot in front of a more primitive robot model, who had been fooled into thinking he was a human. In the previous installment, The Caves of Steel, which I quote below, the character on the right, Elijah Baley, has recurring doubts that Olivaw is, in fact, a robot. Baley has to repeatedly examine proof of his companion’s robot nature. While we are certainly not at this stage of human-machine interaction in the physical world, it appears that we may be approaching that conundrum in our digital environment.

This post could technically be considered “part 3,” because I published the NotebookLM version of the first post in this series a few days ago, BUT I still think that this is the next substantial entry into this conversation from my point of view.

In this post, I discuss more applications that have come to my attention that have the potential to change how human society in general views AI tools, potentially causing them to mislabel them (at least unintentionally and subconsciously, as “agents,” or “persons.” This can impact how we interact with these tools. Our assumptions in this regard can also affect what level of importance we give to communicating with them and relying on their output.

To read part 1, click on the widget below:

Artificial Agency: Characters, Friends, and Social Trends

NOTE: For the “NotebookLM” version of this post, see the widget below:

What is Artificial Agency, Again?

Let us repeat the definition that I talked about in the first post:

The abilities of AI tools, the quasi-human characteristics they have been programmed to have, and the aspects of our cognition that cause us to view them as sentient agents are all combined in my head as a concept called “artificial agency.” Perhaps you could call this “artificial humanity” or “artificial personhood.”

Humans have various characteristics and tendencies that set us apart from artificial intelligence tools. Humans beings can reason. They can process emotions, communicate regarding them, and use pathos in their arguments. Humans can develop emotional and spiritual attachments to each other, which are often called “relationships.” They can also be unemotional and make choices only through reasoning, which entails conscientiously weighing all potential factors of a decision. This involves taking data, facts, and evidence into account and ignoring any relationships or attachments.

Another aspect of being human is the ability to detect and relate to the emotions and needs of others, communicating in appropriate ways depending on the emotions, feelings, and mental state of their conversational partners. This is called “empathy.”

Generative AI tools, while they have been trained to quasi-communicate with human users, do not have these aforementioned abilities. They can only produce what the user desires in a format requested by the user. They draw upon the datapoints and context of their training protocols, weights, and biases to decide the content of their responses. However, networks of computers do not have feelings or emotions. They have no ability to truly empathize with users. I must emphasize this: they only appear to have emotions and empathize with humans. They do so well at first glance only because they have been trained to mimic language used in conversations in which certain keywords associated with emotion were used. As a result of the appearance of emotion, reason, and empathy, some users may be tempted to trust and develop a sort of “relationship” with their AI tools. As I noted in the first article, there are some tools that take advantage of this.

I briefly mentioned Hume, and I will go more into detail about it here. This tool apparently has the capacity to be “empathic” and detect and respond to the emotions that drive users’ communications.

Additionally, since that post, GPT o1 was released. Its developers claim that the tool has the ability to “reason.” They also state that the functions that facilitate reason also give it the ability to think logically and solve “complex problems.”

Another tool, called Nomi, hopes to take the human-ness of AI tools a step further and provide avatars with which users can foster meaningful relationships. Its creators offer “friendship,” “mentor” and “romantic” relationships with AI chatbots.

With all of these tools readily available to us, it can be tempting to think that eventually, humans will not need interactions with each other for meaningful and emotional communication. However, there are still gaps in AI responses and conversations when compared to meaningful human interactions.

I can think of Frasier references regarding both of these aspects of human nature (see the last few minutes of “Space Quest” and the comparison between humans and animals in “Death and the Dog”), but I will do you all a favor and save my exposition of those for my webinars. Season 2, episode 4, of the series reboot comes out next week. Do yourselves a favor and watch it, or at least the original series, on Paramount+ or Vudu.

What Is the AI Equivalent of Reason?

Reason, or logic, is mimicked by generative AI tools through complex computer operations that are hidden from the user. When OpenAI says that GPT o1 can “reason,” what exactly does that mean? Essentially, the “reasoning” and “logic” of GPTo1 consists of passing proposed outputs from LLM to LLM to LLM.

OpenAI states that this method was meant to copy the mental procedure that occurs when a person considers a possible decision from multiple perspectives. In the AI tech world, this is called “chain of thought.”

Some AI prompting experts have been encouraging users to use “chain of thought” in their prompts, in which the user gives an example question or problem, and then proposes a solution along with the reasoning behind why they chose that solution. They give evidence or the mental steps behind their selection.

Now, GPT o1 will engage in that process without any prompting as a result of its reinforcement learning. The outward result of this process is that o1 can recognize and correct mistakes without being prompted, guide itself through smaller steps or tasks that make up more complicated processes, and change its methods of trying to complete a task when they prove to be futile.

Is This Really Reasoning?

This is very impressive, to be fair. Considering if a response is actually appropriate and fulfilling of all user objectives is something that the first few models did not do. It is a great benefit of this new model that the result of one or two prompts will complete a task that used to take six, seven, or ten or more prompts. This will affect not only productivity, but also data privacy, confidentiality, and quality control. “Hallucinations” (or lies, again, let us call them what they are) should be drastically reduced when this tool is connected to the internet and connected to datasets and documents in Custom GPTs.

However, the process of passing data and possible responses back and forth between LLMs and breaking down steps is not quite reason. It could possibly pass as a substitute for deductive logic. But reasoning requires a more broad knowledge of things. It requires connecting materials from both short and long-term memory. It also may require prior experience with certain people, groups, or tasks, which is something that a machine cannot have.

Connecting reasoning and experience with present and possible future occurrences or responses by humans, or to new and novel purposes, requires imagination and curiosity. While imagination and curiosity are not strictly logical, they are aspects of human cognition that drive progress, innovation, and productivity. All of these aspects of reasoning require a human element, an engaged and dedicated user.

Machines are built to accomplish their objective and do nothing else. In the words of R. Daneel Olivaw in Asimov’s The Caves of Steel,

“Aimless extension of knowledge, which is what I think you really mean by the term curiosity, is merely inefficiency. I am designed to avoid inefficiency.”

I suppose what I am trying to say in this section is that while logic involves assessing data and establishing the best fit response due to that data and objectives, reason involves connecting the conclusions arrived at by logical processes to emotional, imaginative, and fluid human elements. Only humans can truly reason.

What is the AI Equivalent of Emotion?

I have a hard time writing this section, because I just do not think that AI tools can write material that sufficiently mimics human emotion, no matter how hard it tries.

Like I stated above, it attempts to use context and content learned from training data and previous interactions to respond in a way that mimics emotion. This may result in the arousal of emotion in some users. So, in a way, the AI tools I explore below may not be intended to mimic emotions. They could be meant to manipulate us into feeling emotions for them by using certain keywords and patterns that our brain processes. Similarly to the workings of the hyper-active agency detection device, when we hear or read those phrases or conversation patterns, we cannot help but feel something.

Hume

The name of this tool appears to be taken from the name of eighteenth-century empiricist philosopher David Hume, and his philosophies are an excellent insight into the goals of Hume.ai. The two main contentions of Hume related to ideas and emotions were

All thoughts that we have arise from the feelings, or impressions, we have about the various entities or physical sensations we encounter.

All ideas and impressions originate in one of two mental processes: memory (through which we analyze experiences to formulate ideas) and imagination (through which we combine preexisting ideas to make new ones).

Hume.ai is unique in that it was not started by an AI developer in Silicon Valley. Its founder is a psychologist who specializes in analyzing emotions and how they are communicated in conversations. According to the Hume website, Hume and other products are meant to facilitate positive emotional well-being in addition to helping users achieve their objectives. In other words, Hume is attempting to complete that second part of reasoning. Hume is so confident that they can achieve these goals that they are exclusively and confidently referring to their main product, Hume.ai, as “empathic AI.” Even though Hume is not capable of being truly empathic, its developers are confident that eventually, it will be able to mimic empathy so well that humans will be just as reassured and confident as they would be if they were talking to another human being.

Hume’s most recent voice-to-voice model, EVI 2, is capable of understanding users’ tone and changing its own tone to ensure the most validating experience for the user. Furthermore, apart from empathic manipulation of its voice, it can also “emulat[e] a wide range of personalities, accents, and speaking styles” to give the user their ideal speaking partner. EVI 2 can also “integrate” with other LLMs, which means that if EVI 2 can become truly empathic, the combination of EVI 2 and GPT o1 could mimic human reasoning and logic in ways we cannot comprehend. In six months from now, this post could be obsolete.

Nomi

So, we have AI a text generator that can mimic logic and an “empathic AI” startup led by a psychologist that might be able to successfully mimic empathy, even if it cannot really feel empathy. This next tool is meant to address another human need: connection and meaningful interaction.

Nomi is a tool that has been around for a while, but it only came to my knowledge a few weeks ago.

Nomi offers male, female, or nonbinary AI companions that can become friends, mentors, and/or romantic partners (non-exclusively, depending on what you need). You can talk to more than one Nomi, and your conversations do not need to be exclusively text. You can generate images that can serve as “selfies” for your avatar if you would like them to be in different locations over time. You can send and receive voice messages. You can send photos of your own. You can even put multiple Nomi avatars in a group and engage with them as you would a real-life friend group text.

Attempting to Outwardly Manifest Reason and Emotion: NotebookLM

NotebookLM was released months ago, but until it received an update that allowed it to create audio discussions with two avatars about uploaded documents or data, it did not seem to attract much notice. As I mentioned above, I put the first article in this series in NotebookLM to get my “podcast.” It not only examined most of the main points of my article, it also added examples (shallow thought they were) that supported my ideas and posited new implications.

The avatars that examine the data and writing of the documents or text you give NotebookLM seem to have consistent ways of communicating with each other no matter what topic you give them. These characteristics provide a sense of nuance to the communication patterns of the two voices and make them seem almost human. They appear to be more spontaneous. These features include:

They ask each other questions.

They are almost worryingly casual in their speech patterns.

They interrupt each other every few minutes, insinuating that they are continuously processing information and forming new ideas.

They persistently, somewhat annoyingly, provide positive feedback to each others’ utterances, which gives the impression that they are actively listening to each other.

Their tones vary widely based on their surprise (they seem to be surprised a lot) and the strength of their “opinions.”

Whenever they make an argument, they back it up with a piece of evidence, no matter how brief.

It seems at first that these avatars are making these observations, which may appear to be astute, on their own. We need to remember, though, that even if the evidence for arguments in this discussion were not explicitly included in the data or information you provided, they could easily be extrapolated and manufactured based on similarities between the training data and your input. More information on data extrapolation can be found in one of my presentations, “Deliberately Safeguarding Privacy and Confidentiality in the Era of Generative AI.” Below is my iteration of this presentation given at the Library 2.0 AI and Libraries II Mini-Conference.

Conclusion

In reading articles about Nomi for this post, I came across an article by Amanda Silberling. She wrote an article about a group chat of Nomis and the insights she gained from interacting. While she mentioned that there are psychological implications of interacting with AI avatars, she also brought up that we are not complete neophytes when it comes to developing attachments to digital conversants:

Though it may seem unnatural to be emotionally attached to an AI, we already form bonds with software — if someone deleted your Animal Crossing save file, how would you feel?

Amanda has her own term for the human-like aspects of AI tools: “faux humanity.” She also refers to another term one of her colleagues uses, “pseudanthropy.” This term is associated with the concept that the artificial humanity of AI agents and tools is not only worth of critical examination, but dangerous to us.

I argue something like this in the last part of my first article, in which I examine Artificial Agency and the Three Laws of Human-AI Machine Collaboration. Devin Coldeway’s perspective, however, seems to be more like the dogmatic commandment in Dune, “Thou shalt not make a machine in the likeness of a human mind” (incidentally, some believe that Dune was written as a response to Asimov’s “unenforceable” Three Laws. “Foundation is Dune with the Bene Gesserit as the hero. Dune is Foundation with The Mule as the Protagonist.”) While his argument of “humanity is dangerously overeager to recognize itself in replica” falls in line with my connection of AI agents with the hyper-active agent detection device, his article supposes that if something can be used for nefarious purposes, it should be removed from possibility for use in any purposes. If we applied that strategy to all technologies with potentially harmful uses cases, we would not have the internet, GPS, or sanitary pads.

Still, as this crowd-sourced Wikipedia article on the Eliza Effect shows, there are hazards of acting on supposed emotions and knowledge of AI tools. No matter what your viewpoint is on generative AI in general, the impact of acquiescing to the “reasoning” and “empathizing” of AI tools can have drastic impacts not only on our human relationships but on our own agency as well. Whether you call it “faux humanity,” “artificial agency,” “pseudanthropy,” “artificial humanity,” or something else entirely, the important thing to remember is that the entity with which we are communicating is always artificial.

References

Coldewey, D. (2024, August 14). Against pseudanthropy. TechCrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2023/12/21/against-pseudanthropy/

Fieser, J. (n.d.). David Hume (1711-1776). Internet encyclopedia of philosophy. https://iep.utm.edu/hume/

Hume. (2024). Home • hume ai. Home Hume AI. https://www.hume.ai/

Kerner, S. M. (2024, September 17). OpenAI O1 explained: Everything you need to know. WhatIs. https://www.techtarget.com/whatis/feature/OpenAI-o1-explained-Everything-you-need-to-know

Nomi. (2024, May 24). Nomi 101: A beginner’s guide to getting started with your AI companion. Nomi.ai. https://nomi.ai/nomi-knowledge/nomi-101-a-beginners-guide-to-getting-started-with-your-ai-companion/

OpenAI. (2024). Learning to reason with LLMS. https://openai.com/index/learning-to-reason-with-llms

Silberling, A. (2024, April 4). I have a group chat with three AI friends, thanks to Nomi Ai - They’re getting too smart. TechCrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2024/04/03/nomi-ai-group-chat-three-ai-friends/

stephensmat. (n.d.). R/dune on reddit: Could the humans in the Dune universe be the first advanced species of our galaxy? https://www.reddit.com/r/dune/comments/1cqasf4/could_the_humans_in_the_dune_universe_be_the/

Wikipedia. (2024, August 20). Eliza effect. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ELIZA_effect