The Phantasm of AI and Elections

Will AI really be that big a player in the 2024 United States elections?

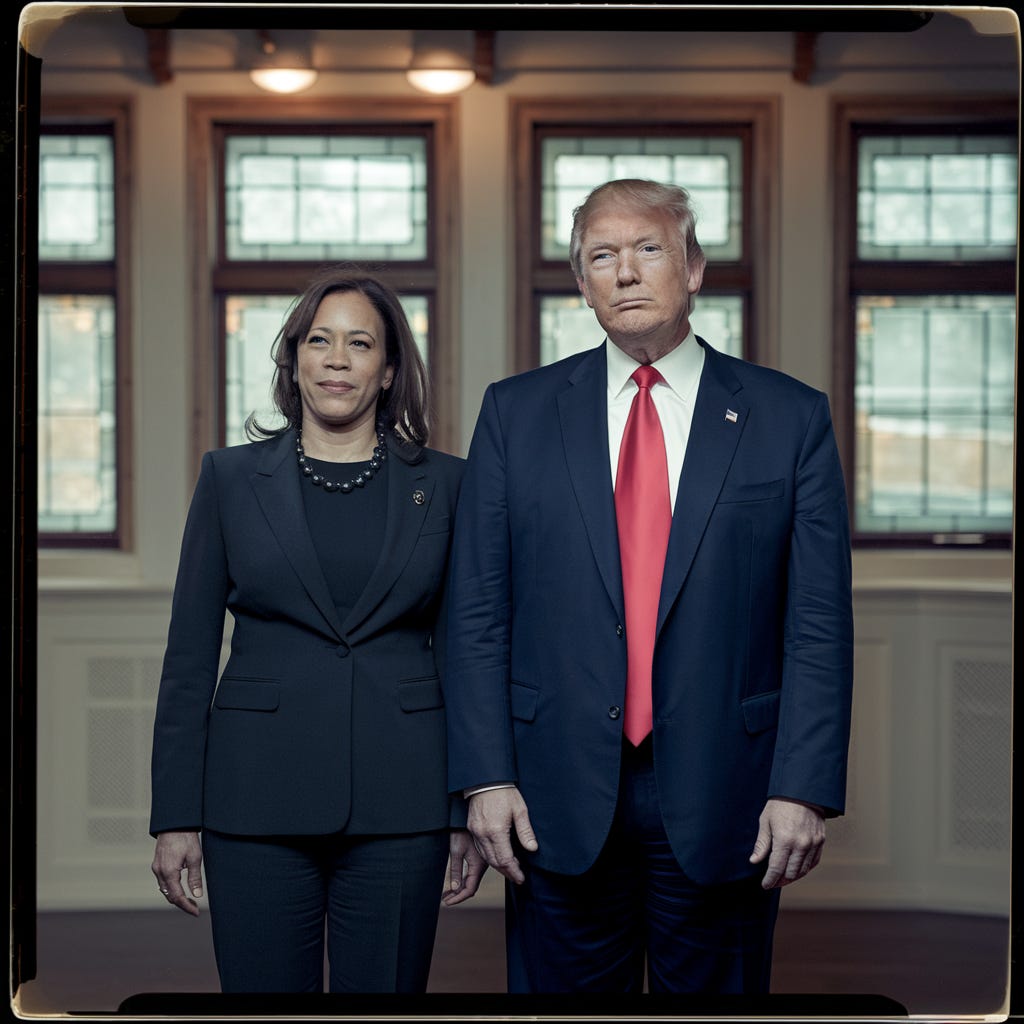

NOTE: I have been hearing the abilities of Claude and ChatGPT to mimic writing styles, and I have always wanted to try my hand. I thought that a post like this, which to my mind is not one of the most important topics, would be an excellent opportunity to showcase AI’s abilities. Therefore, meet the “Reed Hepler Writing Style Assistant,” trained on over a dozen writing samples from yours truly, including the most important and impactful CollaborAItion posts.

Potential AI Interference in the Election Is on Everyone’s Mind

Stefan Bauschard (whom I greatly respect) focuses on the potential for deepfakes to fool people. He is especially concerned about the impact that these tools can have on the upcoming United States federal elections in November. However, there are many more issues at stake with AI literacy and the impact of malicious actors on elections than deepfakes. If we exclusively focus on the drastic examples (deepfakes) we can lose sight of the more subtle corruption being distributed to the American people with AI tools.

The fear surrounding AI's potential to interfere with elections is pervasive as the 2024 U.S. presidential election approaches. According to a Pew Research Center survey conducted just one day ago, 57% of U.S. adults are extremely or very concerned that AI could be used to create and disseminate false or misleading information about the candidates and campaigns. This fear is shared almost equally across the political spectrum, with 41% of Republicans and 39% of Democrats expecting AI to be used predominantly for malicious purposes during the election.

Additionally, confidence in tech companies to prevent the misuse of their platforms is at a low point, with only 20% of Americans expressing any trust in these companies to manage the misuse of AI effectively.

Fear regarding AI deepfakes seems to be help internationally. In 2023, deepfakes were regarded around the world as more threatening than extreme weather and armed war.

Are These Fears Justified?

While the anxiety is palpable, some experts argue that the fears might be somewhat exaggerated. An article from MIT Technology Review suggests that focusing solely on AI's influence may distract from deeper, more systemic issues affecting democracy. The article emphasizes that while AI has the potential to amplify existing risks, such as spreading misinformation, it is not the sole or even the most significant threat to electoral integrity. The real concern, according to this perspective, lies in how AI might be used in more subtle ways, such as data manipulation or quote fabrication, rather than in creating high-profile deepfakes. “In most high-stakes events,” the Tech Review writes, “a multitude of factors… [diminish] the effect of any single persuasion attempt.”

Even If They Are Justified, Deepfakes Are Not the Most Pernicious Threat

Data manipulation, quote fabrication, false or superficial reporting, and other distortion of information are all more widespread and likely errors perpetrated by humans using AI. Creating deepfakes takes time, and most people are not going to take the time to make a deepfake believable. There are certain benchmarks and aspects of real videos or images that make deepfakes hard to pass off, and bypassing those takes a lot of work.

Experts like Oren Etzioni, from the University of Washington, caution that AI-generated content depicting fictional events—such as a fabricated story about a candidate’s health—could spread more quickly and easily deceive the public, leading to severe societal consequences

Data manipulation or information fabrication is much easier to do with AI. With the tendency of humans to not fact-check, false information can be communicated even by people who assume they are telling the truth. This just means that as consumers, we will have to fact-check things we find or read even more deliberately than we have in the past.

How Has AI Use Already Impacted the Race?

Well, in the terms of deepfakes, not much has occurred that would be considered “AI use,” especially if you estimate deepfakes according to their degree to be convincing. Multiple candidates have created deepfake images in support of themselves or to spread other messages, but these are so obviously fake that I will not comment on them or their use.

So far, AI has primarily influenced the election through more conventional means, such as targeted ads and campaign strategies rather than through sophisticated deepfakes. Reports have noted attempts by foreign entities to use AI-enabled tools to spread misinformation and hack into political campaigns, primarily by targeting campaign staff through phishing and other cyberattacks. The influence of AI on the election could, therefore, be seen more in the backend manipulation of data and disinformation rather than in overt digital fabrications.

When we focus on deepfakes as the only major way that AI can be used to impact a race, we forget the more pernicious things like data manipulation, communication distortion, and outright fabrication of quotes and messaging. Videos and images are not the only falsehoods that can be perpetuated by technology, and AI is not the only tool that has been used to perpetuate lies and half-truths.

Campaigns Are Even Wary of Using AI the “Right Way”

Companies such as BHuman, VoterVoice, and Poll the People have introduced AI solutions that reorganize voter rolls, optimize campaign emails, expand robocalls, and even create AI-generated avatars of candidates to engage with constituents virtually. Despite this plethora of technological advancements, political campaigns have shown limited enthusiasm in adopting these tools.

The New York Times highlights that many campaigns are hesitant to openly utilize AI due to concerns over public perception. This hesitation suggests that, despite the potential for AI to streamline certain campaign activities, its adoption is hindered by a fear of voter rejection and a lack of proven effectiveness in achieving objectives.

Only a handful of candidates have incorporated AI into their strategies, and even fewer are willing to disclose their usage of such technologies. Several tech companies have revealed that campaigns agreed to use AI tools only under the condition that the public would never find out about it.

Election Misinformation Occurred Long Before GenAI Was A Threat

If you don’t believe that, ask your parents and grandparents about the April Fools interview of 1983 or the general propaganda techniques that were employed by the United States during the Cold War. Even if there were no half-truths uttered in the news broadcasts or pro-nationalist messages of popular media, their purpose was to push all qualms of supporting one’s country no matter the cost. This gave rise to the tendency to ferret out others who were not doing enough, or appeared to be working against one’s country, and accuse them of being traitors.

We don’t even have to go back into the twentieth century to obtain effective examples of the dangers of misinformation. Judith Miller took advantage of public opinion against Iraq during the prelude to the War on Terror when she published, under the auspices of the New York Times, stories of camps that were creating biological weapons. The resulting scandal became known as “Weapons of Mass Distraction” when independent researchers found that the main points of Miller’s articles had never been independently verified.

These examples illustrate, hopefully, that AI is not the problem. People are. Artificial intelligence is hardly the first tool to be used for nefarious purposes, and it certainly will not be the last.

So What is the Largest Threat of Misinformation?

I spent about half an hour trying to figure out how to put the following into words, but The Financial Times beat me to it. The major threat of AI-generated floods of misinformation is “not so much that voters will trust the untrustworthy but that they will distrust the trustworthy.”

So how do we tell what information is accurate, no matter what format it comes to us in? You know that I am going to mention the SIFT Method here, which I discuss in moderate detail in the following article:

Now that is all well and good, but if we do come across deepfakes, there is another layer of deception involved. No only could wrong information be presented, but it could come through the visage or voice of a person whom we have previously regarded as trustworthy. I still think that this is less of a threat than others do, but on the off-chance that we do encounter believable deepfakes, what some refer to as “counterfeit people,” we should follow the example of examiners of counterfeit money.

Cornell University’s Police Department’s guidelines regarding counterfeit money explains that inspectors look at the feel, “tilt,” flatness, detail, and security features that should be present in authentic currency. They also compare the bill in question with verified bills from the supposed denomination and currency type. The main goal is to “look for differences, not similarities.” It only takes one difference for a bill to be designated as a counterfeit. In a similar (and more intuitive way), we can know if a video or image is a deepfake by what we know of the real counterparts (whether they are real messages communicated by the alleged actors or real images or videos in which they have participated).

Conclusion: Humans Are the Real Threat (As Always)

As with any technological advance, the real threat is not the technology itself. What we really should be worried about is the people who use the technology. And, in my view, if they are stooping to that level, they will probably have done other things that have shown people who they really are. We will not have to wait until they try to create AI deepfakes.

References

Cornell University Police Department, (2024). How to Detect Counterfeit U.S. Money. https://finance.cornell.edu/sites/default/files/detect-counterfeit.pdf.

Dennet, D. C. (2023, May 16). “The problem with counterfeit people.” The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2023/05/problem-counterfeit-people/674075/.

Frenkel, S. (2024, August 21). The year of the A.I. Election that wasn’t. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/08/21/technology/ai-election-campaigns.html

Gracia, S. (2024, September 19). Americans in both parties are concerned over the impact of AI on the 2024 presidential campaign. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/09/19/concern-over-the-impact-of-ai-on-2024-presidential-campaign/

International Center for Journalists. (2018, July 23). A short guide to the history of “fake news” and disinformation. ICFJ. https://www.icfj.org/sites/default/files/2018-07/A Short Guide to History of Fake News and Disinformation_ICFJ Final.pdf

McBride, K., & Simon, F. M. (2024, September 3). Ai’s impact on elections is being overblown. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2024/09/03/1103464/ai-impact-elections-overblown/

Thornhill, J. (2024, June 20). “The danger of deepfakes is not what you think.” Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/bcbbe8af-90c3-48bc-8b16-c9ec57c3abf3.