The Rise of the Machine-Centered World: Postman's TECHNOPOLY and the Development of AI-First Education

Another whole-book summary

Introduction

I’m already going to have an essay right in the one-page introduction:

“Technology does not invite a close examination of its own consequences.”

This was certainly true of the world in the early 1990s... and even more true today. In the 2000s, when digital technologies were first mass-disseminated to the public and put in their PCs, the lengthy Terms and Conditions list of CD use introduced us to the idea that these notices, and the checkboxes associated with them, were nothing but boilerplate language that did not really have an impact.

When they were connected to the internet, and when providers could examine much more data about the users and use patterns, this brought up many issues. However, people were so used to just scrolling by that the providers were able to put in a plethora of surveillance propositions in. Do we remember the uproar when Facebook FINALLY showed us how much data it was acquiring (and extrapolating) about us in the early 2010s, TWENTY YEARS after this book?

AI in Preexisting Web Services

In November 2022, when ChatGPT was released, the whole world acted like the field of artificial intelligence had never existed until that moment—we all hovered around our computers and asked LLMs all types of questions—and feared that the entire field of writing was going to be changed forever.

How did it come to this? It is in part because we were lulled into adopting all sorts of technologies uncritically. Technology and its providers almost always present themselves as a net positive, with little to no reason to worry about its implications. When negative impacts DO appear, they are quickly drowned out by a surfeit of the flashy “benefits,” both real and potential (and sometimes just imaginary).

Postman invokes the names of several major thinkers related to technology (Illich and Ellul, etc.), and then closes with the “catastrophic” proposal that technology will be our “savior” at all times.

Which begs the question: If technology is our “savior” even when there is no physical threat, then what do we need saving from? It seems, then, that technology seems to be positing, or creating, its own problems in society. It convinces us that we need it, or that there is a problem, and then proposes ITSELF as the solution. It is not quite an ouroboros, but more like a mechanical racketeer.

Postman starts were Weizenbaum left off in his COMPUTER POWER AND HUMAN REASON, which I wrote about (a collection of my LI posts, like I will do with this series later) a few months ago:

The Case for Human-Centered Use in an AI-Centered World: Weizenbaum's COMPUTER POWER AND HUMAN REASON in the Age of AI

Photo of Dr. Weizenbaum by Ulrich Hansen, is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=138940

Chapter 1

The Judgment of Thamus was my introduction to this book, and it sucked me in. It’s even better the third time. I talked in several recent posts about the idea that people are offloading their cognitive skills to AI tools as well as social media (in fact, that was one of my longest posts, though not many people mention it.

Practicing Deliberate InfoLit with Various Media...

This post is insanely long, and I’ve already cut more than half of it… you have been warned!

Thamus talks about the dangers of writing, that people will not think themselves but rather rely on what has been written. I could narrowly focus on the similar effects of AI and forums here, but that is not what the analogy is, and we lose something of we focus on the superficial implications of the narrative.

If we apply the lesson to technology in macro, the argument is that there are two negative impacts of every technology: 1. We lose some aspect of our human behavior, and thus we become less human, and 2. We lose some method or pattern of interacting and connecting with other people, and thus, we become less of humanity.

Do We "Bring the Human" to Human-AI Machine Interactions?

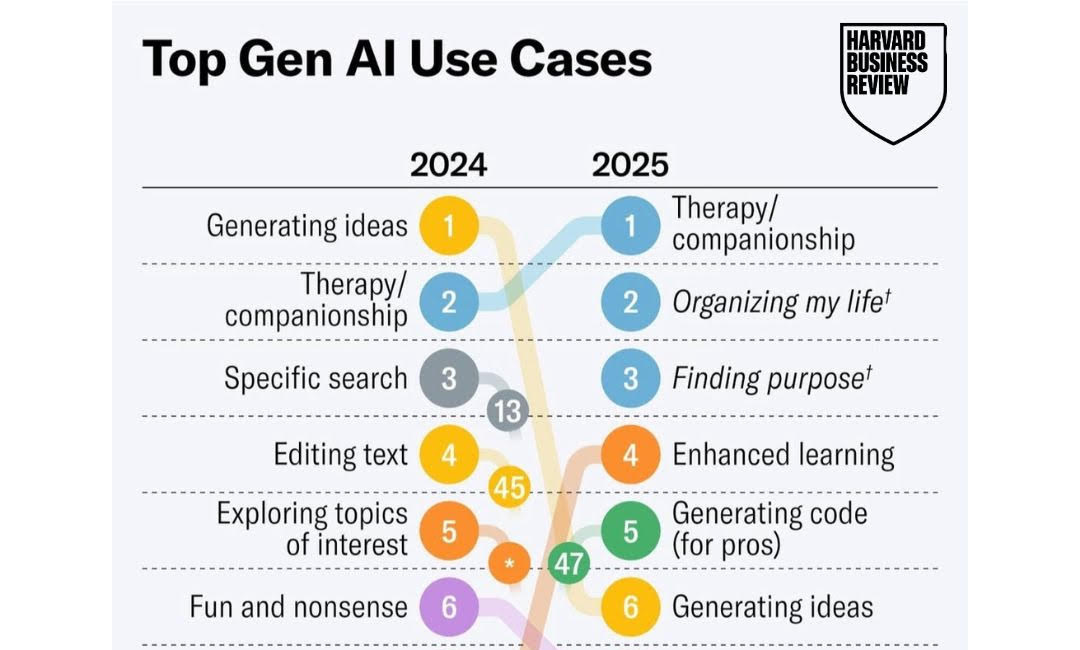

I came across the above image in an email that was sent to me from Harvard Business Review, but it originated in this blog post on the HBR website. Lest we think that HBR is plagiarizing, the author of the post is also the founder of filtered.com . In this post, I am going to combine insights from my own experience as well as the results of the HBR surv…

Postman talks about the dangers of thinking as Theuth (only positive) and Thamus (only negative). There are positives and negatives to each technology, and we must admit both. People who see only positive tend to sing “Go lovely Rose.exe”, and will do anything they can to incorporate the technology wherever possible. Both sides are impossible to escape, but pro-hypists are particularly vocal, attractive, and deafening.

The reality is this: I mentioned earlier that technology creates its own problems, and in the hyper-capitalist consumer world, that is true (we don’t really need to automate everything, we are just convinced we do by advertising and hypothetical opportunity costs that are pressed upon us constantly). However, technology has also solved problems that were not of its own making. Immunizations, telephones, email, have all solved problems of health, communication, verification, etc. However, we can surely think of uses for many primarily helpful technologies that are harmful, at least on a societal level if not immediately to the user.

Postman notes that Freud had some of these arguments, but notes that even the existence of technology, and not its uses, could be a problem. Interestingly for me, Postman distills his ideas into the argument that technology inherently brings about changes in DEFINITIONS, which in turn change how society operates. And that, in turn, changes what it means to be a member of that society, to be human.

Technology, for instance, has had an immense impact if certification and acceptance of contracts. I imagine that the first people who entered into a work agreement did so with handshakes. Now, when I was filling out a contract last week, I not only had to fill out certain fields, but also fill them out in a particular ORDER, and there was software to track that order. Deviating meant the contract would be voided.

Postman brings up the concept of “grading,” and notes that it is only a 200-year tradition, taken up widely after only ONE trial at Cambridge. But now, where would program accreditation and success metrics be without qualitative representations of individual and group success? We have grades, and rankings, and Likert scales. Celebrities are lauded for the number of streams and followers rather than the quality of their work, and production of media follows what will get the most viewers, with little thought to the quality of experience they will actually have, the ineffable soul-nurturing they need.

God forbid we look at the people, the numbers will be fine.

Another example of the effects of conversion of aspects of life into values, which Postman borrows from Lewis Mumford’s TECHNICS AND CIVILIZATION, is the mechanical clock, which was mostly developed to help monks tell time consistently without relying on candles and nails. The mechanical clock told the bell-ringer exactly when to ring the bell for prayers, so some monks would not be earlier or later than others.

So, the problem: monks are not performing devotion precisely throughout the monastery.

The solution: Clearly divide time into equal intervals, and then time everyone by those intervals, so that every person prays after certain intervals, and not by external and subjective means.

The unintended byproduct: Now, EVERYTHING can be assessed by those intervals of time, including productivity, process length, and the idea that TIME, not only LIFE, was limited.

Postman brings up what he calls “collisions” or “attacks” of the new technology on the old. Clocks on candles, newspapers on pamphlets, radio on printed word, television on radio (and still, the printed word), etc.

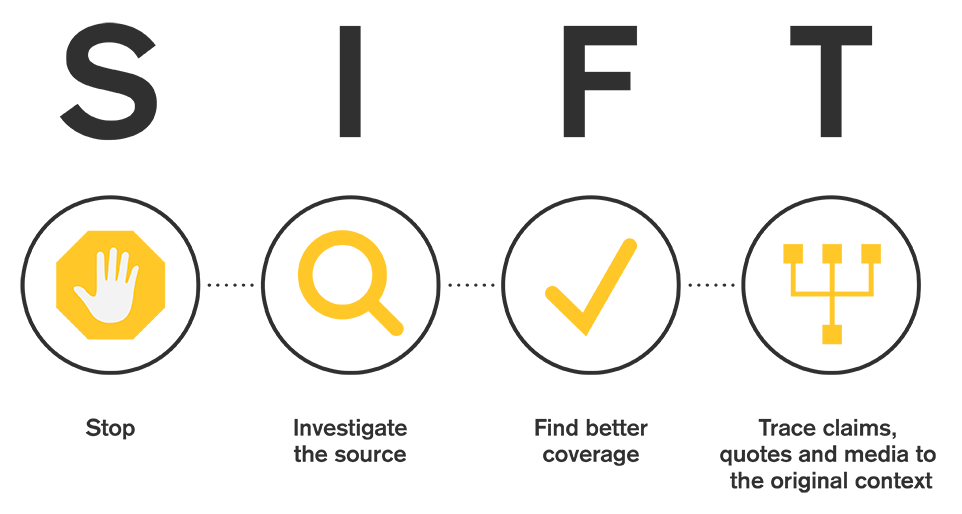

In our age, I could EASILY name other technologies that have attacked these other “new” technologies. Social media on “traditional, mainstream” media, short-form media on long, etc. Mike Caulfield has stated that he believes that short-form video media is more concerning to him as regards information literacy than generated text from LLMs. I tend to agree with him.

I believe that TikTok sensationalizes most, if not all, topics. The platform has no choice--viewers demand the shortest of short-form content--and probably does not want to. Users hate-watch (and duet, and repost, etc.) just as much as they watch out of agreement, which drives traffic. Short-form media is one of the largest threats to information and digital literacy we have today, in all its kinds (Twitter/BSky posts, TikTok). In the framing of Postman, they present short, little, quick bursts of information without encouraging any critical thinking about the emotional, contextual, and narrative context that has been stripped away by the necessity of being brief.

Practicing Deliberate InfoLit with Various Media...

This post is insanely long, and I’ve already cut more than half of it… you have been warned!

Postman talks about the generalization of this idea--that technologies changes not only the person but also the community and the values of society-- as Technopoly.

Chapter 2

In this chapter, Postman categorizes societies according to their purposes and boundaries for using technology. He is quick to point out that these are NOT surrogate groups for an “evolution” of society (societies that we view as “early” or, if we are prone to be ethnocentric, “primitive,” have created more effective technologies at an earlier date than our own ancestors). However, the grouping DOES provoke one to look at similarities in the FUNCTIONS and SOCIETAL ROLES related to technology. This reminds me of the similarities between geographically distant societies noted in the Cognitive Science of Religion.

Essentially, in societies which had religious principles and commandments to control what people did by themselves, they had significantly fewer impulses to do those things using the tools. They had religious rules, or guides, that were more important than the tools. They never considered if they could use tools differently, because they were directed to other things.

Starting in the 13th century, when the church tried to control the technology, or control society using technology, the norms of the world changed. Technology was no longer controlled, or its uses were not implicitly discouraged, by religion. Instead of being religion-dominated, technology and science began to insist on their own space in the world, and slowly and painfully religion (or, the men who controlled religion) gave it up.

This was especially true in cases in which technology directly contradicted religion (or proved it wrong). Galileo’s REFINEMENT of the telescope, for example, proved that the Earth was not the center of the universe, as the church had claimed.

Now, we have shifted (and even more so in the 2020s than the 1980s) to a society in which technology is dominant and more or less controlling society. We are consumed with creating, using, and making new types of uses for technologies.

Postman then goes into a lengthy exposition on Galileo, Kepler, and the development of a science-incorporating society. This is somewhat inaccurate, because he is assuming that technology is ALWAYS used in a responsible, science-informed and best-practiced-condoned way. Technology, however, does NOT mean science in PRACTICE. It SHOULD, in theory, because that is what theory is... preparation for research. But I digress.

Postman promotes the arguments of both scientists that were progenitors of the Stephen Jay Gould’s “non-overlapping magisteria,” in which science and religion are seen as equally valid, but are only limited to speaking on their own subjects. However, they themselves did not completely believe this, as many scientists engaged in scientific belief BECAUSE they believed in God--they viewed their discoveries as FROM God, emanating from Him.

Bacon, who came long after these scientists, thought a lot about the technologies and focused on communicating those to the public. In his view, science was meant to change society. He was one of the first to view man, not God, as the supreme change-maker in the world.

After Bacon came three main views of technology, which all exist in some form today (and the same person may have multiple of these views about different technologies in their life):

1. Technology is evil

2. Technology is a blessing

3. Technology is simply here, for better or for worse

Of course, these views are inherently subjective, because they imply that everyone, at least those with whom we are communicating, have the same definitions or categories of WHAT is evil, what qualifies as a blessing, etc., in order to include technologies in those categories. Thus, technology is associated with cultural values and spiritual and emotional attributes that can eventually be codified in religious or spiritual dicta.

Postman finished Chapter 2 with the idea that, as technology as the prime mover of society, or at least a major one, society came to (in my words) regard AUTOMATION as their chief changemaker and goal, rather than God or a higher quality of living. They focused on developing and using tools and society as effectively as possible, for their OWN SAKE, rather than for their use to society.

Chapter 3

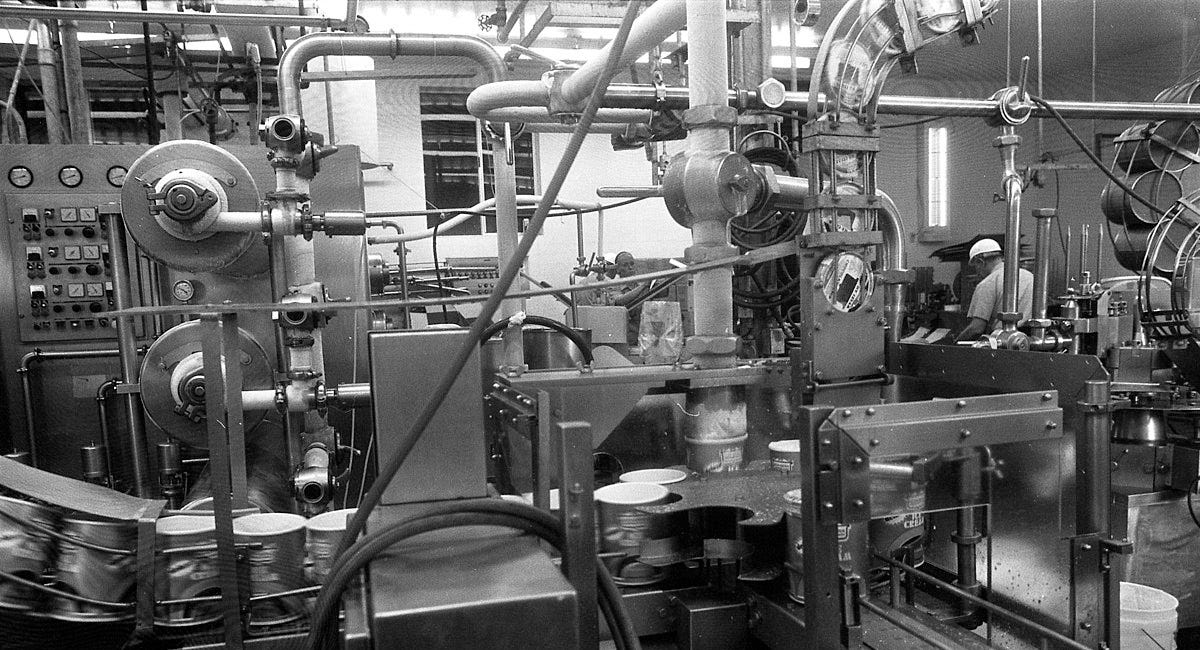

The use of technology to automate previously manual tasks that required human insight and labor, and therefore time, was almost a foregone conclusion in a few decades after the first complex machines were built. Toward the end of the eighteenth century, Europe’s Industrial Revolution sprang from the development of various automated machines related to the textile industry, which simultaneously put many workers out of work while endangering the limbs and lives of those who were trained to replace them.

Not everyone, obviously, had this view. Blake, Milton, Moore, Tolkien, and others have railed against “dark Satanic mills” for one reason or another. Even the “libertines,” who were a literary category noted for encouraging... openness and alternative lifestyles, decried the immorality of these technologies. It was an age in which everyone had strong opinions about the actions of their neighbor, and defended their own actions vehemently.

Postman follows these societal changes further and attributes the rise of the “natural rights” paradigm, the idea that every human was worthy of recognition and protecting, and the necessity of a more egalitarian and accessible education. With the dignity of the individual asserted on their own merits, the importance of certain beliefs and values was decreased. Religious and ideological freedoms were introduced, and society became much more pluralistic. And this, Postman implies, was all because invented technologies presented new, inescapable harms and society decided that all humans should be protected.

Postman here clarifies his argument about technology. Technology results in major shifts of the main beliefs and practices of a culture as it transitions from its predecessor, but it does not completely destroy those beliefs. Some find ways to fit the new technology into preexisting schemata and belief systems, even if they have to revise their beliefs a bit. After all, as Postman said, “it was possible to contemplate the wonders of a mechanized cotton mill without believing that tradition was entirely useless.” In MY words, “not everyone wants an AI religion.”

Techno-Theology: Shall We Fall Down to the Stock of a Data Tree?

And none considereth in his heart, neither is there knowledge nor understanding to say, I have burned part of it in the fire; yea, also I have baked bread upon the coals thereof; I have roasted flesh, and eaten it: and shall I make the residue thereof an abomination? shall I fall down to the stock of a tree?

Nevertheless, the worldviews and belief systems that did not incorporate new technologies were eventually discarded or marginalized, not because they were deemed BAD, but because the impeded PROGRESS and PRACTICALITY. Technology was most important--remember, automation made everyone more efficient--and so a belief system that impeded its use or expansion was not useful to society anymore. It was not a hostile takeover, just a gradual phasing out.

Similar aspects, as I noted in my first few posts, have led to us BELIEVING that our natural rights (to privacy, as a notable example) are not important anymore, because they impede our access to services and programs. I have called this the “commodification of privacy,” and it is one of the reasons that I focus on using

Once again, Postman conflates science with technology. He talks about the Scopes Monkey Trial and, in essence, faults William Jennings Bryan for turning a question about education (science education) into a question about MORALS. Bryan associated evolution (and non-creationism) with immorality and creationism with morality. In a way, this was justified--Creationism sprang explicitly from the religious book from which he derived his morality--and he can be forgiven for conflating a perceived attack on an INTERPRETATION of the Bible for an attack on the MORALS of the Bible.

Postman is either believing that religious belief is incompatible with scientific truth (that religious details can be revised to fit new discoveries of truth) or is examining very effectively the thought processes of WJB. He is really leaning hard into the NOMs of Gould again. I think there is value in this idea, BUT we are going to have to realize that while the INSTITUTIONS have to be separate, the APPLICATIONS OF THEIR TEACHINGS, and therefore the beliefs IN PEOPLES’ MINDS, MUST be combined at some level.

Taylor, whose book I am going to read after I finish this and a rereading of Gagne’s CONDITIONS OF LEARNING, tried to erase the humanity and moral thought processes out of industrial (or, for our purposes, product- or change-formulating) work. Once the essential steps, processes, attributes, etc. of a product were perceived, they used them to explicitly instruct humans, who were MECHANIZED and not required (in theory) to think at all. They became automatons who were not, in the end, autonomous. And this carried over into their social lives and families as well (but this is another story).

Chapter 4

Postman opens this chapter up for a complete attack on the social sciences, as he thinks that they focus too much on how society is now, and how it could be in the future, rather than it has been in the past. I do not think he pays enough attention himself to the utility of history, which could be used to compare to the social science of the present...

Fittingly (and I cannot believe that I missed this the first time I read the book), Postman uses an analogy to state that technology has taken the same place in our society that science research, what Postman called Progress, did in the twentieth century, and that religion did before that: the place of authority. If a technology says it, or has set it in motion, we do not question it--at least, we do not try to understand it.

We have lulled ourselves into a complacency regarding our not-knowing. We focus on the idea that what we do not understand is not understandable, and that we do not need to be informed. So many technologies exist, and thus so many fields, that we are so comfortable with specialization that we avoid general knowledge as it is “outside of our domain.”

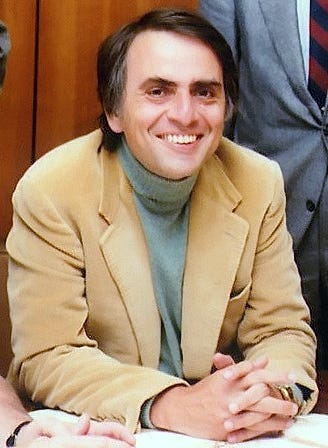

What Would Carl Sagan Think About GenAI?

Lately, I have been thinking about the influence of important people in our lives. I am not necessarily talking about important people on the world stage. I am not even talking about the most important people in any social, religious, or other group of which you are a member. I am talking about the most important people in

In Insta-Research, I talk about a comparable aspect of research tools--databases provided information, but once we utilized search engines, not to mention AI tools, we began to have information overload. We were bombarded, and at that time we began to trust things that others said because we did not have the inclination, if we had the time, to verify.

Chapter 5

This chapter seems to be focused on the argument that modern society, especially for Western civilizations, has developed a sort of digital materialism. We have become dependent on technology, and information provided by it, for our decisions, our opinions, our actions, etc.

How many of us do not know what we have on the agenda for the day, but for the digital calendar that we have on our phone or our email app? How many times do we check the news... on our phone, or social media, to know if downtown is safe, if the government is not shutdown, etc.? Our society, and most people in it, RELY (if only emotionally and psychologically) on INSTANT and IRREFUTABLE information access, and that through an increasing number of technology.

We tend to become basketcases when we lose access to our technology (even though we back it up). For example, our car keys are battery operated and open our car doors just by proximity. Do we remember that they also have physical mechanisms to open our car door?

In a similar way, many people today (young AND old) do not know how to read analog clocks--if their digital clock goes out, they have no idea what time it is (the news says that it is only younger people, but I know an educator who, self-deprecatingly, said that she and other teachers breeze through that module of their class because THEY THEMSELVES do not know how to do it proficiently).

I can talk about maps, too--if Google Maps were to go *kaput* tomorrow, how many of us would be able to go to MapQuest and follow directions, or buy a map, or (God forbid!) ask other people for directions?

Postman attributes this to the breakdown of the processes by which we store and record information, or (as a processing mechanism) WINNOW OUT information we do not wish to know or admit. Courts have lengthy and complex processes that eventually result in the jurors ONLY considering the NARROW subset of all possible information that is SPECIFICALLY relevant to the case. College catalogues have descriptions and codes that ensure that students ONLY take courses that are related to their needs and desires. No more general studies (except we have tried to circumvent this rigidity by requiring general courses). Families operate on the idea that parents and older siblings are the arbiters of information for the youngest members. We are responsible for both teaching and protecting our children and siblings.

No one can know and believe everything, and so we have all developed or adopted various theories (religious, political, social, educational, etc.) to explain what to admit, what to exclude, and how the information we admit is contained in our theories. Bureaucracies, in which the expertise of every person is VALUED, or at least lends itself to the formalization of one’s role in an organization, have exacerbated this trend. The institution does not function unless every person KNOWS their appropriate technology and uses it EFFECTIVELY

Chapter 6

In this chapter, Postman discusses the idea that technologies of today are centered around the idea that all we need is ANSWERS and SOLUTIONS. So, it presents those to us, while CREATING THE QUESTIONS AND PROBLEMS in our minds to prepare us to accept its offerings.

Do we really need a machine to tell us when our coffee is done? Or, for that matter, make our coffee for us? And do we need to have our phones notify us when our laundry is done or when our package has arrived? Half the time, we get it hours after it is dropped off, anyway. Before you say, “Reed, you’re a Mormon, you don’t know about coffee.” That is true. But I have had my fair share of hot chocolate. Half the time, when people get machine-brewed coffee, they let it sit and cool for at least ten minutes afterward. It would have been quicker to make it manually,

Postman notes the well-documented anomaly in which American doctors took around ten times more diagnostic reports (for example, X-rays) than their European counterparts, and are more likely to prescribe more technologies as well. There appears, at least to Postman, to be a mentality in the country of “if we have the technology, we may as well use it.” In fact, if we do NOT use it, we may be seen as incompetent or intransigent.

Take librarianship in the past THREE years alone. I co-wrote the only available OER generalized book on Library and Information Science in 2022, a combination of my work, work by Teri Fattig, the former director of the library at which I work, and the late David Horalek. A year after I wrote it, one of the main reviews of the book included among its claims that I was an unreliable author simply because I MENTIONED ChatGPT. Two or three months ago, I was requested to talk to another library system, but ONLY about the “positive effects” of genAI tools. I refused, and they relented, and I talked about “Practical AI Ethics.”

It may be that we need to remember Asimov’s Three Laws and their implications for technology and its providers (who are, let us recognize, IN CONTROL of the narrative furthered by the technology. The analogous rules for technology companies would probably be a type of “social contract,” that they are not supposed to take advantage of the public, and we all know how that has worked out.

In essence, technologies and their companies have violated the Zeroth Law BEFORE they violated any others: They harmed human society in general by impressing on our minds that we NEED to use technology AND have our decisions and choices VALIDATED by technology, or we are guilty of malfeasance or, WORSE in our current culture, ignorance.

Chapter 7

Postman notes the impact of the computer on society, noting that one critic said it was as “momentous” as the Gutenberg press. Why was this? It was the impact that the technology had on the spread of information. Whereas the Gutenberg press spread words around, and in various forms, words were not FINDABLE unless you knew where to look for them. The index, created in the sixteenth century, helped with that. However, the COMPUTER found words FOR the user, in milliseconds. You did not need to know context, structure, or how to navigate the text. The computer did not care about those, either. It parsed everything into data and then found that data, and stripped it of its context.

A few decades after the calculating, data-retrieving, and data-presenting computer was developed, users began to refer to this type of tool as “intelligent.” We started theorizing about “artificial intelligence,” and almost simultaneously began alluding to “thoughts” and “beliefs” that these machines possessed. For example, McCarthy proposed his infamous “three beliefs of thermostats.”

This perspective, as Postman dances around throughout this chapter, is mistaking the PRESENTATION of a perspective with the INTERNALIZATION of that perspective, the belief in its validity. Once people conflated those two, it was only a matter of time before we regarded machines as MODELS, SURROGATES, and then REPLACEMENTS for human minds. Then, we started doing the reverse: considering humans as MACHINES.

The Case for Human-Centered Use in an AI-Centered World: Weizenbaum's COMPUTER POWER AND HUMAN REASON in the Age of AI

Photo of Dr. Weizenbaum by Ulrich Hansen, is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=138940

Since we have internalized our “nature” as a machine, and... machines as humans, we have inferred abilities, or facts, that do not exist. For example, we think that thermostats cause the weather; we also say that we MUST be wrong if a computer disagrees with us. Furthermore, we are FOOLS if we choose not to involve computers in the most mundane decisions.

Postman brings up Bolter’s argument that the computer could become a new type of book (ironically, I am reading this on a Kindle). GenAI has emerged as a type of bastardization of that suggestion--it DOES “expand... the tradition of writing technologies,” but I doubt it “enriches” it.

Postman then discusses the negative implications of technology, specifically computer, dependency on research and scientific inquiry. He notes that multiple voices have essentially said that the computer and other “automatic” (for the early 1990s) calculating and communicating machines have engendered an expectation that everything will be immediate and machine-calculable. Researchers, they fear, will not want to do the actual research. Will this extend to law, doctors, or even education? It has, in some ways, already spread to education.

Parenthetically, in the first few sessions of the OLC Accelerate 2025 Convention, BOTH sessions brought up the potential for AI tools to review student submissions and provide automated feedback as a completely positive proposition with no negative aspects. At LEAST the second session included the command to create an extremely detailed list of criteria and factors to assess, rather than a simple two-sentence prompt.

Chapter 8

Postman focuses now on what might be called the “technology of language,” which is the idea that the language we invent as a tool to name and direct actually NAMES AND DIRECTS US. He does not say this in as many words, but I will. We created a system to describe, order, and categorize, and in so doing we limited our understanding of the world. Postman particularly looks at the way we query and assess understanding, and claims that the form and structure of the questions we ask presuppose certain things about the human brain and offer subliminal assistance for potential respondents. For example, someone who may not be able to fill in a blank answer MIGHT be able to answer it through Multiple Choice simply by process of elimination (we have all done this).

Incidentally, and I do not know if Postman analyzed this, the whole purpose of multiple-choice exams was to create a standardized, efficient way of assessing knowledge through quantification of student scores. Machines were the inspiration for this change, and before long machines were used to grade these tests, which is why ScanTron is still in business.

Postman continues to focus on the structure of the question, and examines the idea that the WAY we ask questions, and the questions we choose to ask, limit what the answers can be. Similarly, the way that we use the number “0,” which led to the development of statistics and, eventually, to its misapplication in eugenics, has shaped our perspectives and beliefs about the world. “0,” in and of itself, is not a bad thing. But when one uses it to signify the absence of value or lack of presence of a cognitive or behavioral aspect, subjectively determined, then it is a very dangerous symbol, or technology, indeed.

This is to say nothing of the damage that misapplication of numbers and quantification has done to society in the realms of politics, religion, and social sciences (ACTUAL social sciences). Polling tries to quantify our opinions, which are by nature ineffable, and has significant biases on which question it asks and how it asks them (”Yes” and “No” answers leave no room for ambiguity or fluidity). Furthermore, polling only asks about opinions, not informed ideas and knowledge, which members of the public might have. Thirdly, these are taken IN AGGREGATE, and these misrepresentations of superficially reported and inadequately acquired opinions are all lumped together into reports, potentially with biased interpretation and loaded chart titles. Government, public programming, social efforts, are all done according to these polls, and then people are dissatisfied with the results.

Religion has this problem as well, at least my religion (the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) does. Every six months or so, if it is not continuous, members of the Church are “randomly selected” (how random this actually is has been a topic of debate for years) and asked a long survey of questions about their beliefs, opinions on Church programs, etc. Church leaders decide whether they want to change the programs or expressions of doctrines, or if they want to go another route and become more rigid or vocal about obedience or being accepting of the “Lord’s will for the Church.” They called this Correlation.

This is not to say that I am dissatisfied with the Church, or that I am not a faithful Mormon. I am, if I am a bit unorthodox. BUT, this is about the ADMINISTRATION of the Church, not the doctrines or the teachings of Christ. As multiple of the Brethren and Seventies have noted, the Gospel is perfect, but the Church changes as external aspects and realities change, to carry the perfect Gospel in different forms throughout time and to different cultures.

Why do I have this brief interlude about the “Mormon Church”? Even divine organizations are influenced by terrestrial technologies and constructs--they have to be, they are mediating between the human and the divine.

Postman then connects most of the APPLICATIONS of technologies that we use today to the military and its training academies. The management system and written report chain, for example, was created to organize MILITARY academy reporting, and then administrators who had worked at that institution travelled to non-military institutions, bringing the rigid style with them.

Before long, we were operating in hierarchical systems in as alien an environment as the RAILROAD, not to mention the changes that took place in non-profits, religions, even volunteer and civic groups, which have all been inculcated to create and present reports to SOMEONE on a regular basis. Are there benefits to this? Yes. But now it is not done out of necessity, but because “other organizations do it like this, so we should too.” I saw a person in a leadership position become disaffected from the institution because she “did not know Robert’s Rules of Order,” as if that was an essential part of management or board participation.

Chapter 9

This chapter is a very long description of how faulty and how dangerous social science can be, and while Postman has excellent points, as a researcher of education efficacy, and a (apparent) “scholarly practitioner” or “theorist-practitioner,” as I have been called this past weak,” I do not think that social sciences are as bad as he claims. However, we will focus on what he says in the context of the message of his book.

Postman views social science as a type of technology, as a method or system for viewing society. If management and multiple-choice questions are technologies, then I suppose social science can also be included in this paradigm.

Essentially, Postman takes social scientists (from anthropologists to psychologists) to task for prioritizing the narratives they have created either through “naturalist” participant-observation or through controlled experiments (for which he uses the extreme Milgram experiment as an example). They insist on quantifying aspects of behavior or patterns, and then they interpret those patterns based on their own preconceived notions, and then they use those interpretations to 1. create a narrative of the whole, and 2. assign value or morals to the actors in that narrative. Thus, we come from values to values through a (to Postman) subjective process, hardly “real science.” Postman is not alone in this view.

As I write this, I am sitting in the aftermath of a presentation on discussion boards and how they can be improved to be less “boring.” The solution for two of the three presenters was... new technologies; an instructional designer who had no idea what the instructors had said (he had a meeting before) completely delegitimized the second instructor’s technology as “not really contributing much to the discussion process other than a slightly different interface.” Again, this occurs when we insist on looking at society through a technology lens. We stop asking “what are people looking for,” and start thinking, “how can we use technology,” and start looking for OPPORTUNITIES rather than SOLUTIONS.

What happens when we take the social science view, Postman warns, is that we see problems everywhere, and try to describe WHAT the problems are, rather than see IF there are problems. We have already decided they exist. This is, partially, why we kept calling non-Western civilizations “primitive” until the 1960s.

As seems to be the central aspect of the Online Learning Consortium Accelerate Conference, and a sub-theme of the Association for Educational Communications & Technology (AECT) International Convention, of 2025, Postman is saying that STORY, or NARRATIVE, COMMUNICATION is the most important part of expressing ideas and entrenching them in society, of exposing others to new ideas and helping to shape how society operates.

STORY, as Ceredwyn Alexander stated in her pre-conference workshop, is CENTRAL to genAI optimal operations. Not only does story encourage students to participate at the beginning of modules, but the most engaging assessments for students are those that involve creating narratives and viewing those from others.

Once again, Postman invokes religion and argues that sociologist are merely repeating moral and societal lessons or messages that have been told for centuries, except their “religious texts” are created by themselves or their predecessors: data and its analysis. He suggests that the REASON that social science narratives are based on “scientific data” are because that technology, and Technopoly, demands it--only things associated with data are worth considering and are relevant. Therefore, to keep relevant, social scientists acquire, or record, numbers to base their narratives on. According to Postman, social scientists come with their own preconceived notions. If the data follow those notions, that is great. If they go against, then there is some type of bias or external influence that is skewing that data. This is a bit oversimplistic, but his point is somewhat arguable.

Surprisingly (a VICTORY for me!), comes to the conclusion that, if we are focusing on the fact that social sciences (and, in many instances, the “hard sciences” today) are focused on creating a specific narrative, then studying ALL narratives, EVEN fictional ones, are beneficial to society and to professionals in all types of fields. In fact, fictional narratives could be MORE beneficial because they have not been biased by the love or influence of technology. They are more human; they have emotion, and morals, and things that an objective, data-obsessed technology does not and can never have.

Postman finishes the chapter by providing a conclusive description of his “Scientism”: the hope and believe, and actions that spring from them, that science can provide a kind of moral guide for society in the vacuum left when technology ostensibly “overthrew” religion. However, religion (pure religion) does not rely on rules, procedures, and data-defined classes of people or ideologies. It allows for variance and emotion. Science has procedures and rigidity, which will turn all of humanity into nonautonomous automatons if taken to extremes.

One of the main conceptions of science, especially that kind that overturned the hold of the Catholic Church, was that there was ONE scientific solution, and all other proposals were false. If there was an aberration, that was either because a new method for the experiment had been discovered that was more effective (in which case the “definitive answer” was changed), or the experiment had been done wrong.

With the advent of social science, and other “softer” sciences, that was no longer true. There are many answers to questions depending on how they are framed (we have already examined the impact of questions). Depending on one’s social or psychological view, one looked at a societal or behavioral anomaly in different ways, and therefore came to different answers. Fittingly, religions also multiplied (at least in the public perception) as well as non-religion. Political ideologies, some of which publicly proclaimed their roots in certain psychological or societal theories, also multiplied.

Postman again talks about Freud and his notable internal debate on the impact of the belief in God on society. Freud says that in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, belief in God is holding society back from “Progress” (again, the development of technology that we seem to think is so important). Postman claims that we are in a similar situation now regarding science--whether or not science says something is feasible, technologists (think genAI providers) do it anyway.

Chapter 10

And here, we get to the root of communication, education, instruction, and all other types of information dissemination: action. The root of all of these is to get someone to do something, or change a pattern that they had been doing before, or NOT do something that they had been doing.

In Technopoly, according to Postman, sacred and profane symbols alike are judged and used according to one metric: utility. Will the presence of certain symbols, particularly if they are placed in alien contexts, jolt the viewer into doing whatever the target action or pattern is?

Postman then talks about education, and comments on an idea that has been brewing for the last 30-sumodd years, if not 40 years: instructional technology. Granted, Postman is not an instructional designer, and not an instructional technologist. He thinks that some applications of technology are not useful when they really are (and he attacks Merrill’s 3Es, even if he did not know who Merrill was). However, he DOES get at the main problem with most educational or instructional technology integrations: we have lost sight of our learning objectives and goals.

Sadly, Postman takes the fact that we have lost sight of our goals to mean that we do NOT have learning objectives, that we as an entire field have no focus. However, we DO have focus. We have just tossed theory aside in favor of technology.

He then notes one of the many problems with the “Classics” or “Great Books” view, which was a proposal by Ed Hirsch and others to combat the information glut of increasing technology and resource availability: the Great Books list keeps expanding, and (as we can see in the penultimate month of the first quarter of the 21st century) the TYPES of media keep expanding (in case you hadn’t heard, Vine is coming back, as a completely “new” type of social media).

Postman concludes the chapter by lamenting that since the Great Books plan has failed, and religion and science are being forsaken in favor of machines, we have no “unifying narrative” or “unifying cause” for the country, except perhaps war. However, do we really NEED a unifying cause for the entire country, especially since we are so pluralistic? Globalism has its own narrative (admittedly, it is borrowed largely form Technopoly, since globalism was made possible by technology in the first place), and with the increase in international collaborations, it appears that that narrative is transcending national narratives, which are quickly appearing as tribal as the narratives they replaced in the twentieth century.

The purpose of education, which Postman fails to realize, is to teach, and learn, to help or teach other people. It is to create an individual, group, community, nation, and world that is comfortable with the sharing of ideas and the betterment of society as a whole. Perhaps this is the Mormon side of me “contaminating” my academia, but we are all meant to help and support each other, to come together.

Chapter 11

Fittingly, I am writing this chapter’s summary as I am listening to the opening keynote of the Online Learning Consortium Accelerate 2025 Conference by Amanda Bickerstaff.

In one of the first slides of the conference, she uses an axis-less chart with an arbitrary “Human Parity” line at the top of the graph, with all “abilities” of genAI tools moving toward the top at various speeds and rates. Admittedly, there are multiple of these abilities that are not yet claimed to have reached that line. We are not yet claiming that AI has “parity” on every level with humans.”

However, we come back to the issue that I noted a few months ago, and that Postman discussed a few chapters ago. We are quantifying EVERYTHING about what it means to be human. There was also no indicator of what exact numbers were represented by the lines. Also, why is it a straight line? That just skews everyone’s metrics. However, we could hardly have twenty graphs on the slide, so that is a good compromise.

In essence, Postman calls for people who USE technology, but that do NOT let it determine their values. They do not, in a phrase, let their tools turn their choices into decisions. They communicate with other human beings, turning into a COMMUNITY, rather than remaining content to be alone with their technology.

Postman posits that, to combat Technopoly and enculcate values necessary to create these technology-independent thinkers, schools, as a model of information institutions, should address the moral and intellectual core beliefs: how they view society, how they view themselves, how they view the PURPOSE of life.

Personally, I believe that the Church and the family are the places that one should learn these things--that was the reason they existed in the first place--but Postman’s message is still the same in that case: people need to be confident and firmly grounded in what they believe so they will not be blown about by every wind of techno-theology.

In this presentation, Bickerstaff suggests that AI tools can be used for brainstorming, “instructional design” (if we go to my Facebook groups, they would say “that’s not instructional DESIGN, that’s instructional DEVELOPMENT!”), and other instructional and learning tasks, and then she talks about the MANY issues with hallucinations and privacy and effectiveness, and that “young people are using AI in the worst possible way.”

So, why is she saying that we can use it? She has deliberately thought out a system, a way, an INTENTIONAL PLAN, to keep users grounded in reality, in values, and in their identity as students and digital citizens. She discussed the article “Your Brain on ChatGPT” and actually talked about the real point of the article: if students do the work and put their own cognitive skills into writing and ideating BEFORE they use AI tools, then the AI will “collaborAIte” with us rather than “automate.”

She closed with an absolutely BRILLIANT video created by a group of students, which I wish I had a link to. A student loses sight of who he is and what his responsibilities are because he keeps offloading his cognitive AND creative responsibilities to ChatGPT. He keeps gaining rewards from the resulting superficial products that are produced from this facade, until an earnest opportunity comes to him which requires unmediated, earnest effort.

Postman closes his chapter with the notion that what we have perceived as a war between “religion” and “science” is not real. In fact, “the Big Bang theory of the creation of the universe... confirms in essential details what the Bible proposes as having been the case “in the beginning.” And so, we do not need to become angry with another narrative, or technology, or group that has a different story than our own. We simply need to be confident in our beliefs, in our values.

In order to ensure that students are learning what they need to in their field BUT ALSO in the world at large, he posits something akin to what John Curry called “joining the conversation.” We need to communicate our ideas, and receive others’ ideas. He also suggests that we need to “teach every subject as history... and history as ‘histories’,” which, to me, means discussing ALL views on a particular subject, and how those ideas evolved, combined, fell away, and become what we have now. In other words, we need an education that follows the pattern of Steven Johnson’s HOW WE GOT TO NOW. It is all about discussing perceptions, values, ideas, beliefs, and arguments CRITICALLY. Discuss historical events in context of movements, theories, and contrasting viewpoints to discourage what Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie called the “danger of a single story.”

In the words of Viciente Alexandre,

“take off your shoes and go in. Go into the swarming square.

Go and discover your own face in the torrent that claims you.

Small, miniature heart! Blood that longs to beat

And become one with the harmonious heart that soaks it up!”

He also suggests that either “every teacher teach semantics” or that there be a specific semantics “course,” which I would say is a bit beyond the mark: maybe reserve that for Master’s degrees (which we essentially do when we have a “foundations” course in ANY field). It would be an interesting course of which to be a member, however! I am intrigued by that thought!

How does this relate to Amanda’s presentation? She placed users in the CENTRAL role in genAI use cases; and therefore placed the onus (appropriately!) on the EDUCATORS of students as future users. We are responsible to teach them to be critical, literate, and prepared to question and propose, to love and be loved, to BRING THE HUMAN.

Are you earnestly prepared?

Didn't expect such a clear-eyed look at our digital complacency through Postman's lens. Your point about being lulled into extensive data collection is so accurate. From a public policy standpoint, the implications for informed consent are truely immense, a critical challenge we face with LLMs.