What Would Carl Sagan Think About GenAI?

As One of the World's Greatest Science Voices, It's Interesting to Ponder His Reaction

Lately, I have been thinking about the influence of important people in our lives. I am not necessarily talking about important people on the world stage. I am not even talking about the most important people in any social, religious, or other group of which you are a member. I am talking about the most important people in individual lives. These may in fact be the same people as are important to the world or to your group. For example, Mr. Rogers is one of my personal heroes (I still listen to his songs occasionally on Spotify). Another one of my heroes is Gabriel Faure, a French Impressionist composer who composed what must be the most beautiful Requiem in the history of the musical form. I also have religious and ideological heroes, whom I will not share here.

When it comes to science and technology, though, I have a wide variety of heroes who contradict each other… a lot. Ironically, most of my favorite science commenters are creators of science fiction. Many people have heard me quote Frank Herbert about the Butlerian Jihad and the command of Dune’s Orange Catholic Bible, “Thou shalt not make a machine in the likeness of a human mind.” Another favorite quote is from Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot about the massive Machines that analyzed and directed humans in producing materials and resources considered by the Machine network to be necessary for human survival:

”The Machine is only a tool after all, which can help humanity progress faster by taking some of the burdens of calculations and interpretations off its back. The task of the human brain remains what it has always been; that of discovering new data to be analyzed, and of devising new concepts to be tested.”

Then, of course, we have one of the world’s great archives pioneers, Schellenberg, who clearly stated that “The use of modern gadgetry cannot supplant the use of proper techniques and principles” (1975).

Who Was Carl Sagan?

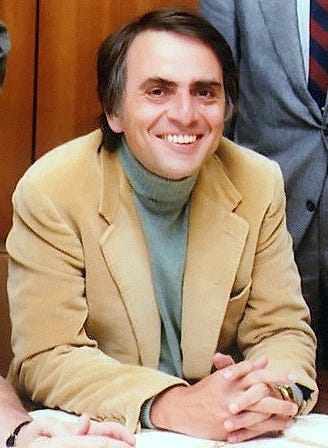

One of the commentators whom I know was qualified to comment on actual science, though, was Carl Sagan. One of my first introductions to him and his work was on his excellent television show Cosmos. He explained the massive, complex, and unknowable universe in simple and understandable language that was almost like music. There was something about his cadence that seemed calming, like an Enya song, or a speech on deciding not to remain angry by Mr. Rogers, or a lesson on the joy of painting by Bob Ross.

Sagan, as can be assumed by the title of his series, mostly focused on astrophysics and cosmology in his own practice. However, the way he carried out his work illustrated a high standard of skepticism and following the classic scientific research process. He was a strong proponent of this as well. In one of his later works, published a year before his death, he stated that “science is more than a body of knowledge; it is a way of thinking.” (1995, p. 25). In the same paragraph, he stated that he was worried that changes in public consumption of information (in “30-second sound bites”) was contributing to a “celebration of ignorance.”

Throughout his life, Sagan attempted to bring scientific ideas to the common individuals, out of the domain of the scientists and their jargon. He also sought to influence policymakers to incorporate scientific ideas in their policies and follow data. When his predictions were wrong, such as the prediction that Kuwaiti oil fires would cause massive economic destruction in Asia, he admitted it. When he was hypothesizing about possible occurrences, such as the possibility of humans interacting with extraterrestrial life, he was clear that he was speaking his own opinion. His position as a popular science communicator with best-selling books clouded that disclaimer, but he still made his listeners aware of his suppositions.

As a scientific researcher and commentator, Sagan does not seem to be a likely candidate to concern himself with religion. However, he did so as one of the world’s most outspoken “Skeptics,” and promoted his own kind of spirituality called “Skepticism” or “Scientism.” This was a type of science- and data-fuelled agnosticism mixed with a supposition that a deity existed in the sum of scientific laws. Perhaps, he thought, there might be a God who created and influenced the physical world by those laws. But there was no way to know, and so he preferred to think of God as “not behind nature but as nature.” (Sagan, 2007, p. 14).

Forgive me for the comments regarding religion, but they are related to my point about his “Skepticism” which he valued so much. You’ll see why this is important later.

What Does This Have To Do With AI?

Artificial Intelligence has seemingly taken the world by storm. We are constantly bombarded by advertisements, research papers (high- and low-quality), use cases, conference, unconferences, and social media posts about artificial intelligence. Pro-hype and anti-hype influencers seek to sway people to “their side” and combat each other with strong and weak arguments. This technology has provoked, if not a revolution, then certainly a revitalization of communication. When previous edtech companies and tools were released, it did not seem to cause that much of a ruckus.

Now, it seems as though every person and group identifies themselves by whether or not they support AI in their field, and “how much is enough” when handing work off to AI. We have workflows, checklists, best practices (which we need), frameworks, and all sorts of advice. Some of these seem to be well thought out, but others (even those from reputable organizations) seem to be haphazard and only thrown together out of necessity. Forgive me in writing in generalizations, but I do not want to besmirch anyone. I honestly believe that most people writing these arguments, statements, and posts are acting in good faith.

At the same time, I think that we need a little more skepticism than we are using when we interact with AI. In my opinion, we need even more skepticism with AI than we need with other types of technology. Specifically, we need to seriously consider why we are using AI (and whether or not the AI will actually help us fulfill this purpose), and how much we trust its output. Perhaps, there is a third type of skepticism that we need, toward ourselves. How much are we truly handing off to the AI tool? Are we truly in control, or are we letting it make decisions for us? It seems we have come a long way from the 1970s caution by IBM that its computers “must never make a management decision.” I am not saying that we should not use AI to process data or analyze management tasks. But we should not ask it what to do. AI, as my friend Steve Hargadon says, is for “research, not conclusions.”

What Did Carl Sagan Say?

So what would Carl Sagan, one of the preeminent science communicators and Skeptics, say about generative artificial intelligence? Well, he actually did say a little bit about it! In one of his articles for the Natural History magazine of the American Museum of Natural History, Sagan discussed the possibility of “networks of computers” acting as psychotherapists that were more efficient than humans:

”No such computer program is adequate for psychiatric use today, but the same can be remarked about some human psychotherapists. In a period when more and more people in our society seem to be in need of psychiatric counseling, and when time sharing of computers is widespread, I can imagine the development of a network of psychotherapeutic terminals, something like arrays of large telephone booths, in which, for a few dollars a session, we would be able to talk with an attentive, tested, and largely non-directive psychotherapist” (Sagan, 1975).

Did you note the Skeptic undertones of his discussion of this issue? He opened the entire discussion of the possibility by stating that “no such computer program is adequate… today.” He managed expectations, at least for the present. Many of us (particularly with solutions to sell or promote) start with the possibilities and then later say, “well, we don’t know if this is going to work for certain.”

Another aspect of this quote that I like is that he mentions that the AI psychotherapist will already have been tested (and presumably found reliable).

As a side note, I appreciate that he used the term “attentive,” as it brought to mind the relatively recent AI paper by Google, “Attention Is All You Need,” to mind.

What Else Might He Say?

In another of his articles, Carl Sagan talks about the features and benefits of his “Skepticism.” After he discusses the different belief systems of humans and why they exist, he notes that there are always people who will try to take advantage of these human beliefs and try to sell something. Interestingly, he seizes on the desires of people to talk with their loved ones after they have passed away. Enterprising people could promote dubious products to “facilitate” this, he warns (Sagan, 1987, p. 3). There are currently one or two startups to quasi-facilitate this with generative AI.

He also refers to frequent claimants to extraterrestrial communications. Whenever he sends specific, complex questions for the Visitors to answer, he never gets a response. On the other hand, if he requests an answer to a vague, general question, like “Should we be good?” There is always an answer. “Anything vague they are extremely happy to respond to, but anything specific, where there is a chance to find out if they actually know anything, there is only silence” (Sagan, 1987, p. 5).

Midway through this article, he clarifies that he is not completely skeptical. There needs to be a balance between being skeptical and open to new ideas. “It’s okay to not be sure… It’s okay to reserve judgment” (Sagan, 1987, pp. 11-12).

Above all else, though, I think he might refer to one of his most thoughtful lines in his Cosmos show and book, and remind us that we may never know exactly how generative AI works:

“But the brain does much more than just recollect. It inter-compares, it synthesizes, it analyzes, it generates abstractions. The simplest thought, like the concept of the number 1 (one), has an elaborate logical underpinning. The brain has its own language for testing the structure and consistency of the world.”

Why Do I Care what Sagan Thinks?

Well, I am glad that you made it this far. My purpose for this post was not to promote Sagan over actual AI scientists. He studied the cosmos, not neural networks. However, his commentary and work promoted the healthy use of skepticism, which I think is key to a balanced perspective on generative AI.

I hope that we can all eventually come together and find that balance, test new and old ideas, and remember that no matter the dangers of technology, we are the ones who must be in control. If, as Carl Sagan says, “We are a way for the cosmos to know itself,” perhaps AI is a way for us to know ourselves.

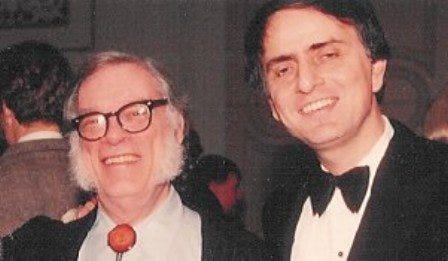

A Longer Side Note: Asimov and Sagan… and an AI Pioneer

Since at least the late 1960s, Carl Sagan and Isaac Asimov began writing each other and reading each other’s work. They regularly sent reviews in letters to each other, such as this one from Asimov to Sagan: “One thing about the book made me nervous. It was entirely too obvious that you are smarter than I am. I hate that.” (in Maggio, 2000, p. 20).

In his autobiography, Asimov declared that Sagan was only one of two people whom he viewed as having a superior mind to himself. Incidentally, the other one was Marvin Minsky, who founded MIT’s AI research labs.

References

Sagan, C. (January 1975). “In Praise of Robots.” Natural History. American Museum of Natural History. New York, N.Y., Volume LXXXIV, pp. 8-23.

Sagan, C. (1987). “The burden of skepticism.” Skeptical Inquirer, vol. 12.

Sagan, C. (1995). Demon-Haunted World: Science as a candle in the dark. Ballantine Books.

Maggio, R. (2000). How They Said It. Prentice Hall Press.

Margulis, Lynn; Sagan, Dorion, eds. (2007). Dazzle Gradually: Reflections on the Nature of Nature. Chelsea Green Publishing. p. 14.

Schellenberg, T. (1975). Modern Archives: Principles and Techniques. University of Chicago Press.